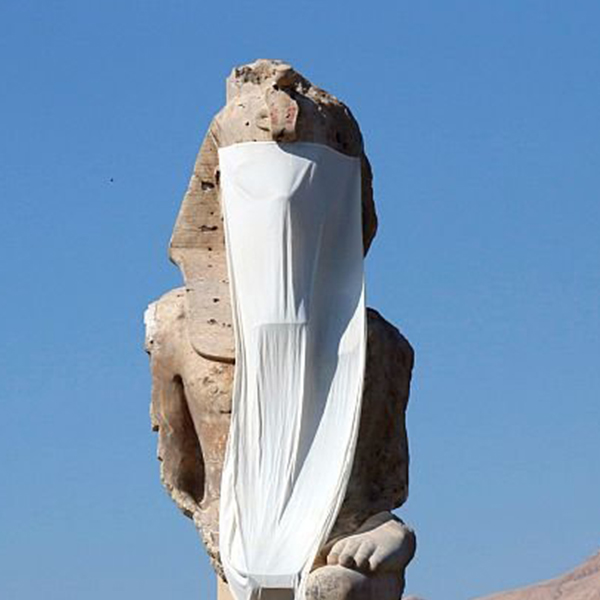

Bandit's Roost

In 1870, 21-year-old Jacob Riis immigrated from his home in Denmark to bustling New York City. With only $40, a gold locket housing the hair of the girl he had left behind, and dreams of working as a carpenter, he sought a better life in the United States of America. Unfortunately, when he arrived in the city, he immediately faced a myriad of obstacles. One was attempting to live among some of the greatest wealth disparities in American history.

Like the hundreds of thousands of other immigrants who fled to New York in pursuit of a better life, Riis was forced to take up residence in one of the city's notoriously cramped and disease-ridden tenements. Living in squalor and unable to find steady employment, Riis worked numerous jobs, ranging from a farmhand to an ironworker, before finally landing a role as a journalist-in-training at the New York News Association.

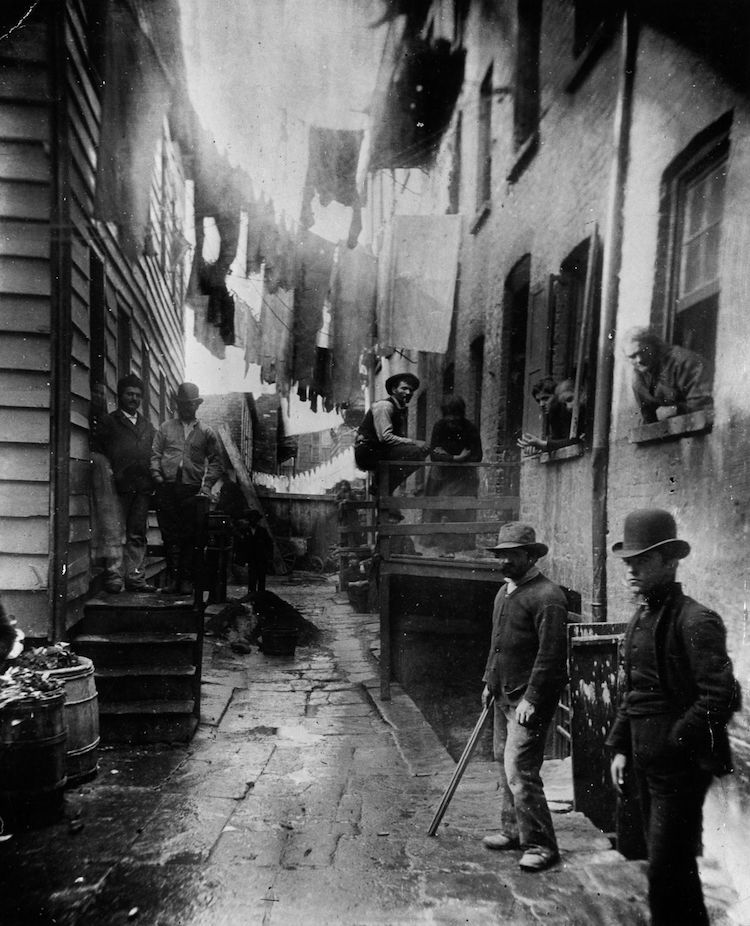

As he excelled at his work, he soon made a name for himself at various other newspapers, including the New-York Tribune where he was hired as a police reporter. Faced with documenting the life he knew all too well, he used his writing as a means to expose the plight, poverty, and hardships of immigrants. Eventually, he longed to paint a more detailed picture of his firsthand experiences, which he felt he could not properly capture through prose. So, he made a life-changing decision: he would teach himself photography.

Portrait of Jacob A. Riis

Riis soon began to photograph the slums, saloons, tenements, and streets that New York City's poor tenants reluctantly called home. Often shot at night with the newly available flash function—a photographic tool that enabled Riis to capture legible photos of dimly lit living conditions—the photographs presented a grim peek into life in poverty to an oblivious public.

In 1890, Riis compiled his photographs into a book, How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York. Featuring never-before-seen photos supplemented by blunt and unsettling descriptions, the treatise opened New Yorkers' eyes with raw depictions of urban slums.

“Long ago,” he wrote in the book, “it was said that ‘one half of the world does not know how the other half lives.' That was true then. It did not know because it did not care. The half that was on top cared little for the struggles, and less for the fate of those who were underneath, so long as it was able to hold them there and keep its own seat.”

Since its publication, the book has been consistently credited as a key catalyst for social reform, with Riis' belief “that every man’s experience ought to be worth something to the community from which he drew it, no matter what that experience may be, so long as it was gleaned along the line of some decent, honest work” at its core.

Making Social Change By Showing the City Slums

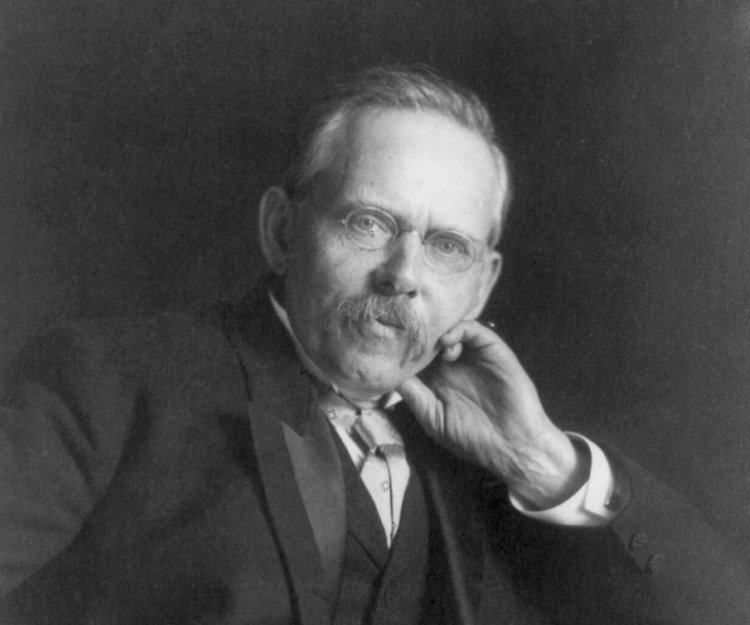

“Police Station Lodger, A Plank for a Bed”

Perhaps ahead of his time, Jacob Riis turned to public speaking as a way to get his message out when magazine editors weren't interested in his writing, only his photos. Thus, he set about arranging his own speaking engagements—mainly at churches—where he would show his slides and talk about the issues he'd seen. Though this didn't earn him a lot of money, it allowed him to meet change makers who could do something about these issues. Notably, it was through one of his lectures that he met the editor of the magazine that would eventually publish How the Other Half Lives.

Once How the Other Half Lives gained recognition, Riis had many admirers, including Theodore Roosevelt. Though not yet president, Roosevelt was highly influential. In fact, when he was appointed to the presidency of the Board of Commissioners of the New York City Police Department, he turned to Riis for help in seeing how the police performed at night. While out together, they found that nine out of 10 officers didn't turn up for duty. After Riis wrote about what they saw in the newspaper, the police force was notably on duty for the rest of Roosevelt's tenure.

Riis was also instrumental in exposing issues with public drinking water. In a series of articles, he published now-lost photographs he had taken of the watershed, writing, “I took my camera and went up in the watershed photographing my evidence wherever I found it. Populous towns sewered directly into our drinking water. I went to the doctors and asked how many days a vigorous cholera bacillus may live and multiply in running water. About seven, said they. My case was made.” His article caused New York City to purchase the land around the New Croton Reservoir and ensured more vigilance against a cholera outbreak.

His writings also caused investigations into unsafe tenement conditions. This resulted in the 1887 Small Park Act, a law that allowed the city to purchase small parks in crowded neighborhoods.

Jacob Riis' Legacy

“Twelve-Year-Old Boy Pulling Threads in a Sweat Shop”

Riis' work became an important part of his legacy for photographers that followed. As a pioneer of investigative photojournalism, Riis would show others that through photography they can make a change. American photographer and sociologist Lewis Hine is a good example of someone who followed in Riis' footsteps.

In the early 20th century, Hine's photographs of children working in factories were instrumental in getting child labor laws passed. Riis' influence can also be felt in the work of Dorothea Lange, whose images taken for the Farm Security Administration gave a face to the Great Depression.

Jacob Riis' interest in the plight of marginalized citizens culminated in what can also be seen as a forerunner of street photography. Acclaimed New York street photographers like Camilo José Vergara, Vivian Cherry, and Richard Sandler all used their cameras to document the grittier side of urban life. In their own way, each photographer carries on Jacob Riis' legacy.

Photographer Jacob Riis pioneered social reform through his photographs of everyday life in New York City's slums.

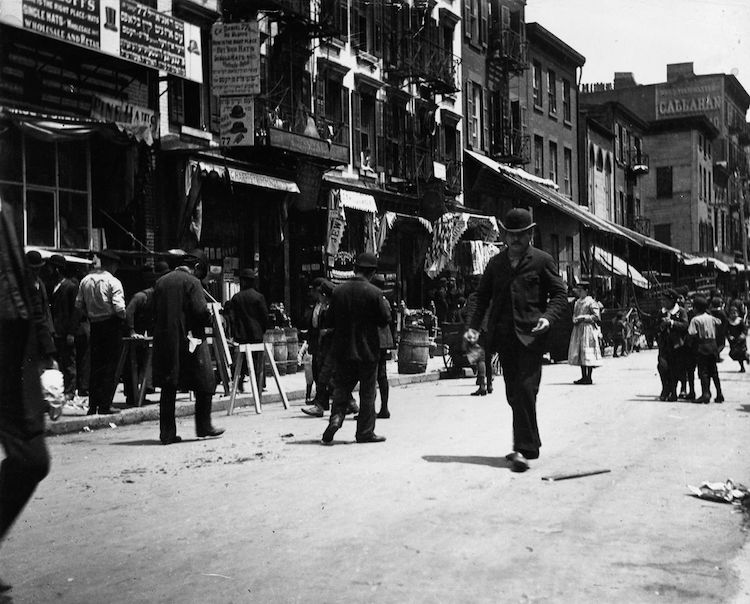

Hester Street

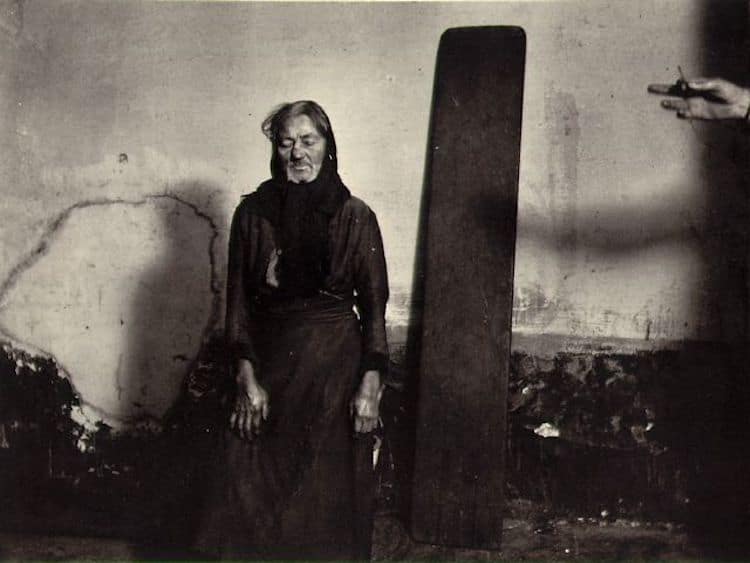

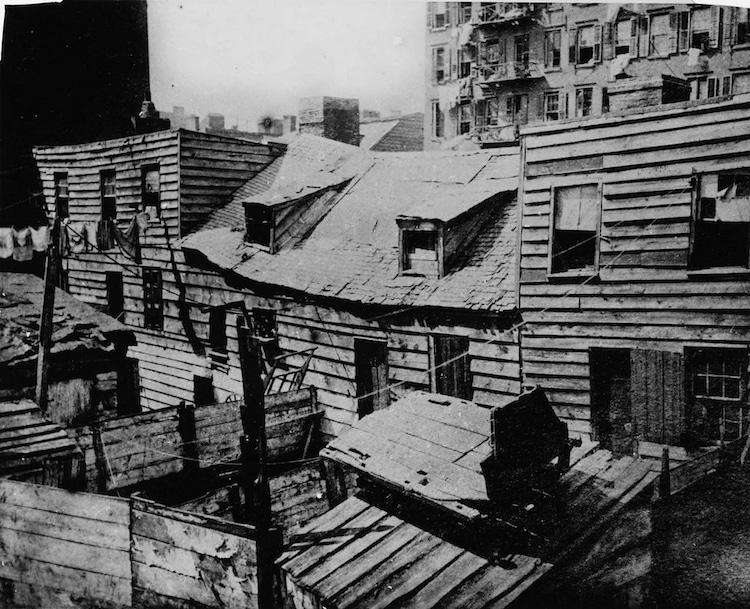

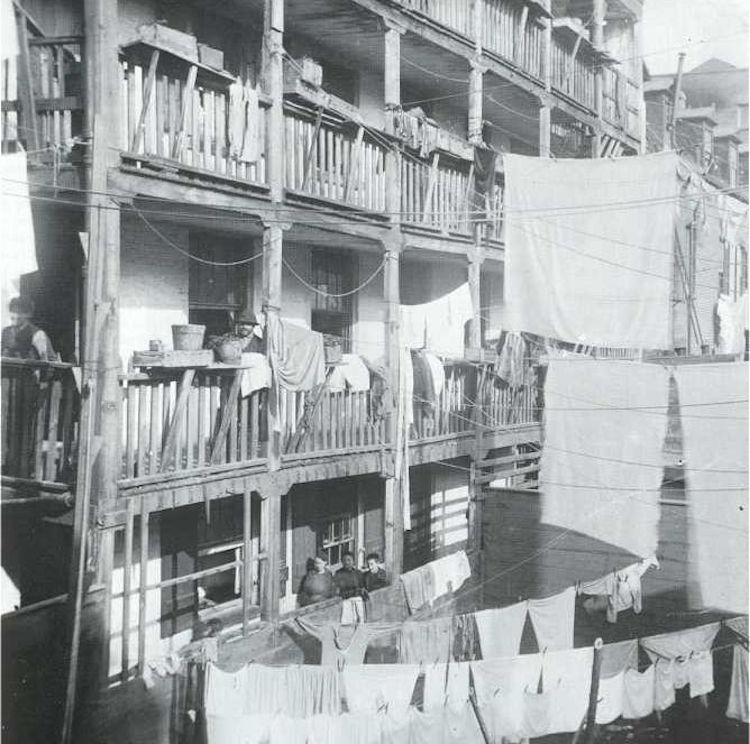

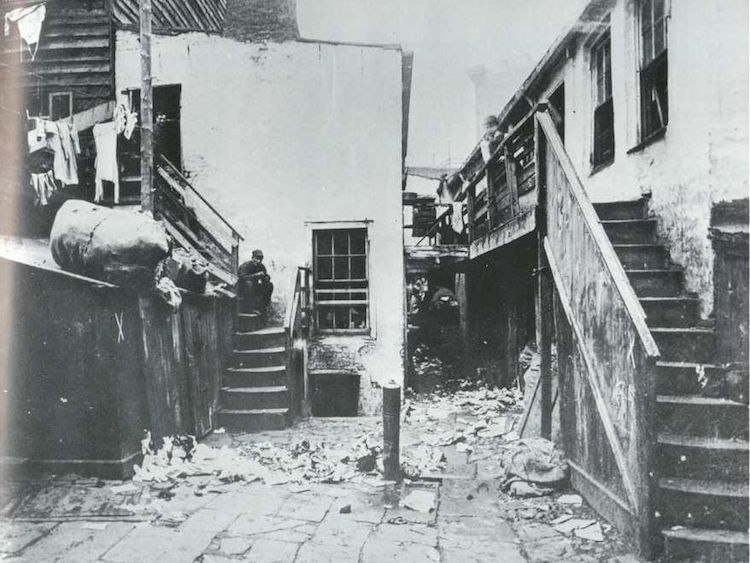

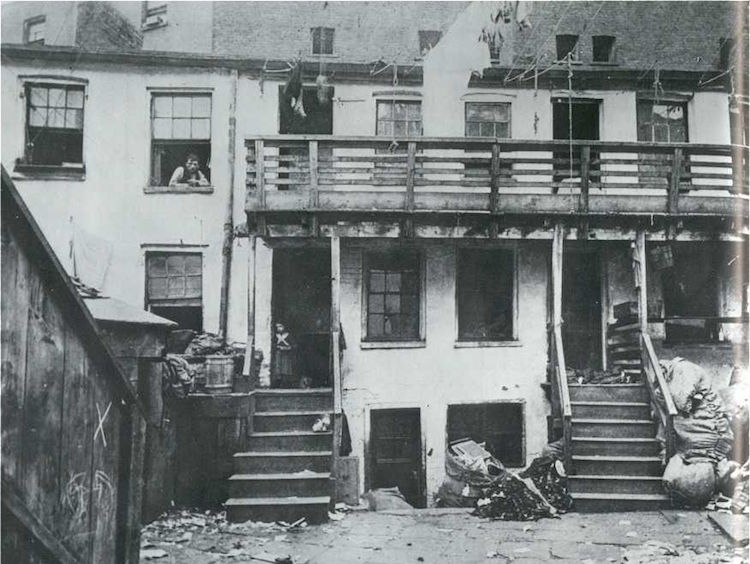

Riis often photographed the decrepit conditions of the tenements.

Dens of Death, New York

An Old Rear Tenement in Roosevelt Street

Bottle Alley, Mulberry Road

Bottle Alley, Mulberry Bend

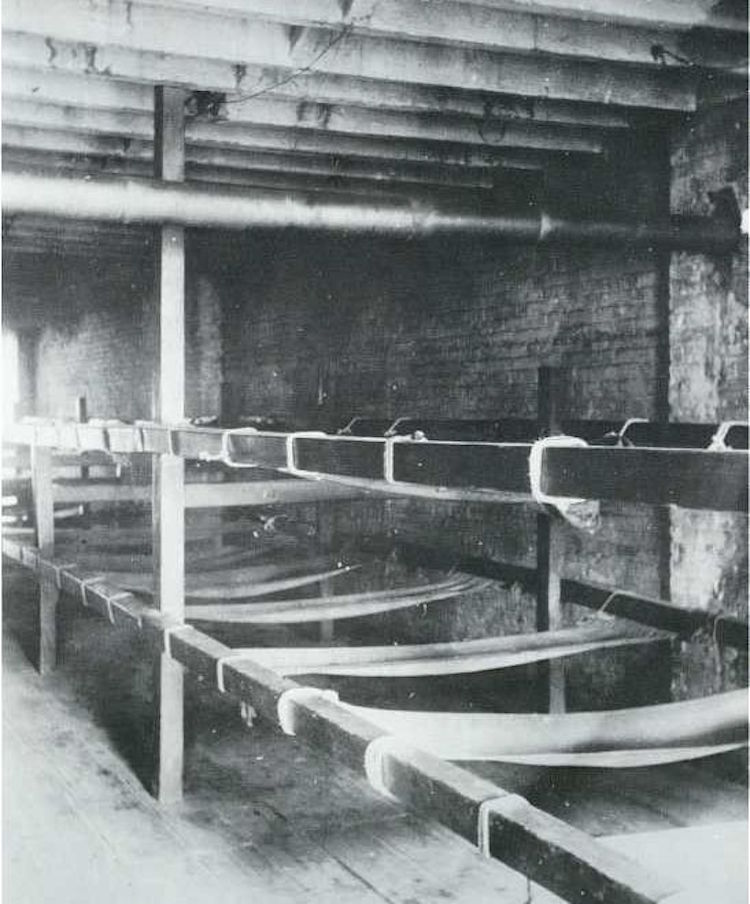

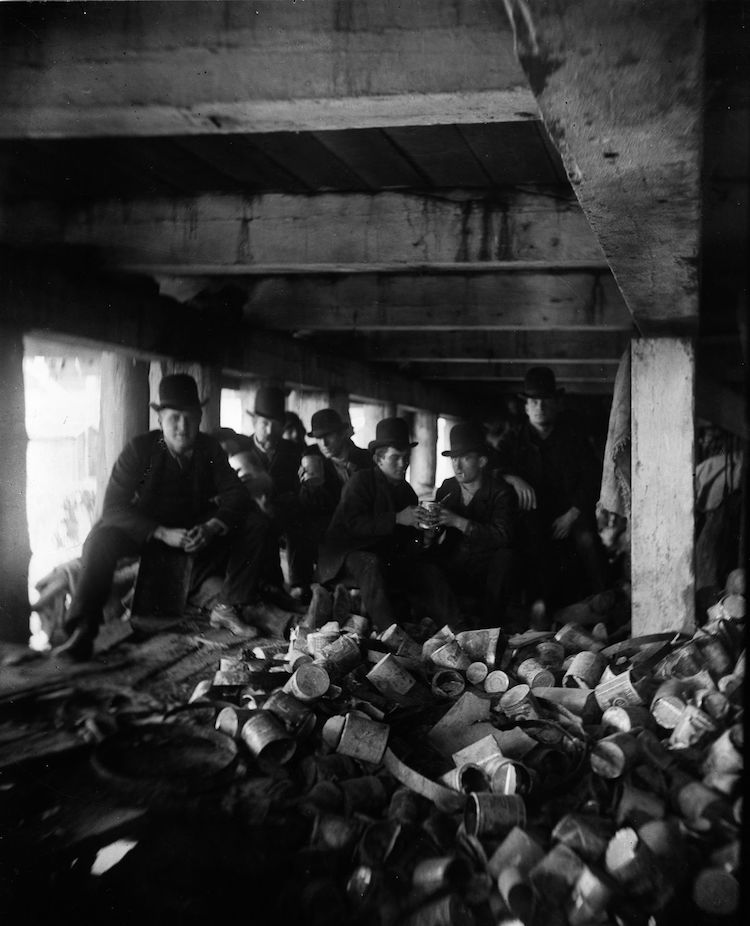

Bunks in a Seven-Cent Lodging House, Pell Street

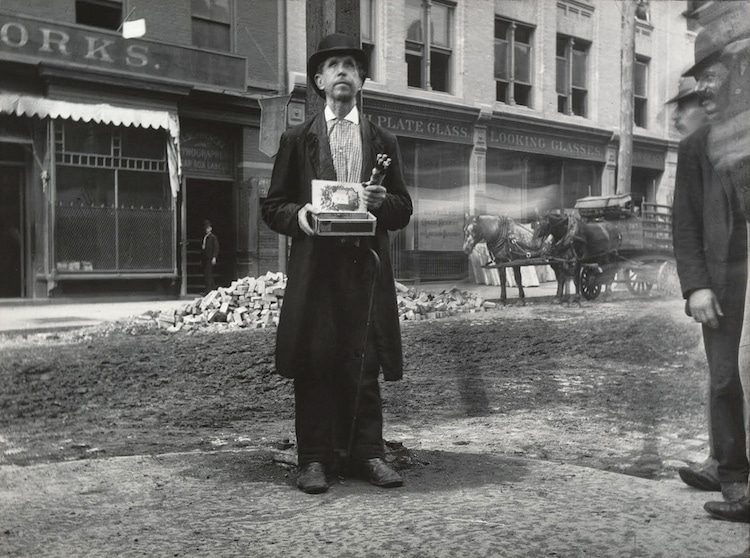

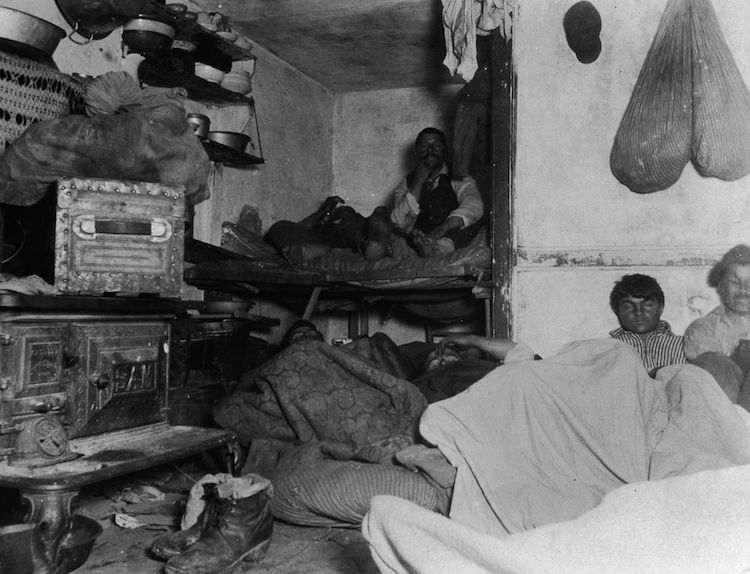

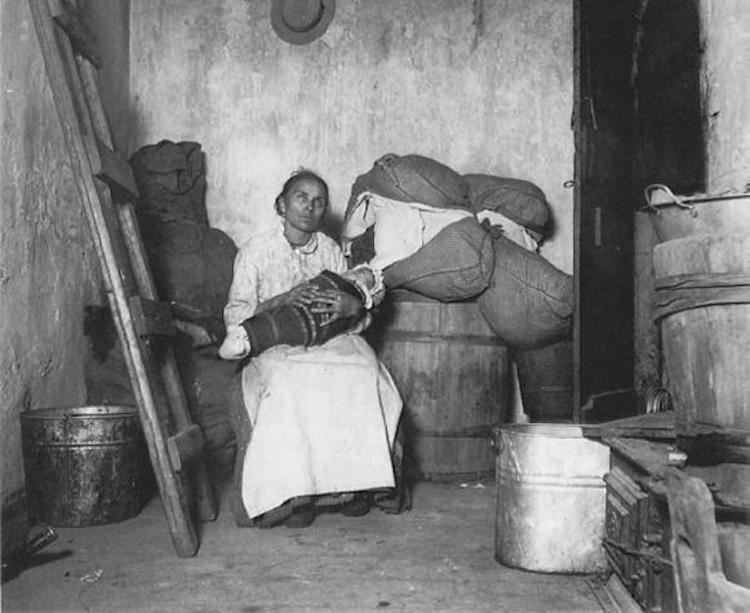

Additionally, his photographs include many upsetting shots of immigrants and poor people simply struggling to get by.

Room in a Tenement

Blind Beggar

Five Cents Lodging, Bayard Street

Bohemian Cigarmakers at Work in their Tenement

Fighting Tuberculosis on the Roof

The Short Tail Gang Under a Pier

Family Making Artificial Flowers

In Sleeping Quarters – Rivington Street Dump

Home of an Italian Ragpicker

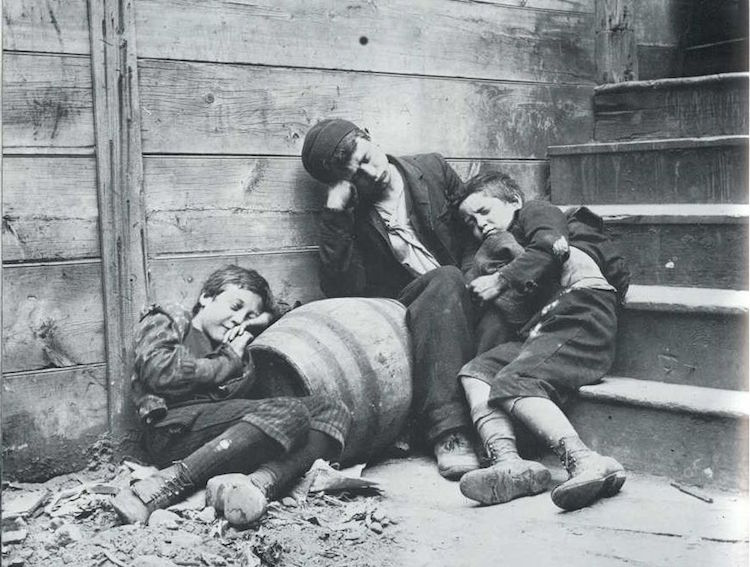

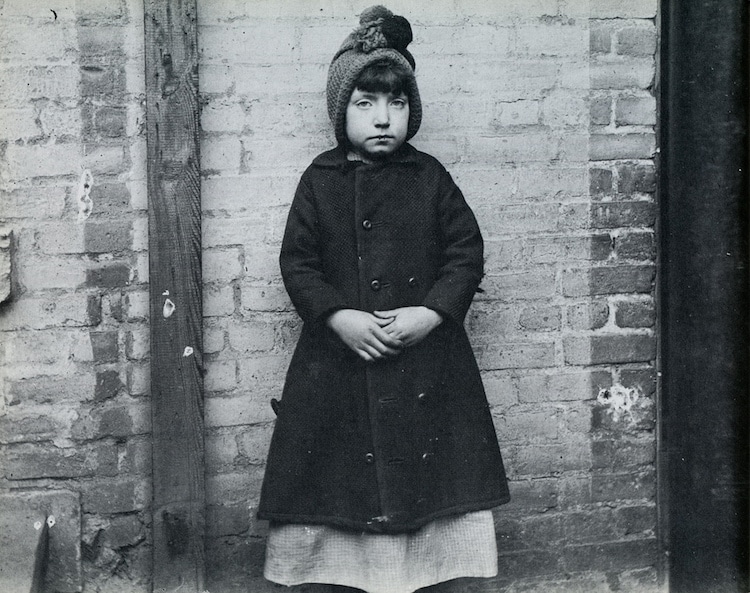

…Including impoverished children.

Minding Baby, Cherry Hill

Didn't Live Nowhere

Drilling the Gang on Mulberry Street

Children's Playground in Poverty Cap, New York

In the Sun Office, 3 AM

Girl and a Baby on a Doorstep

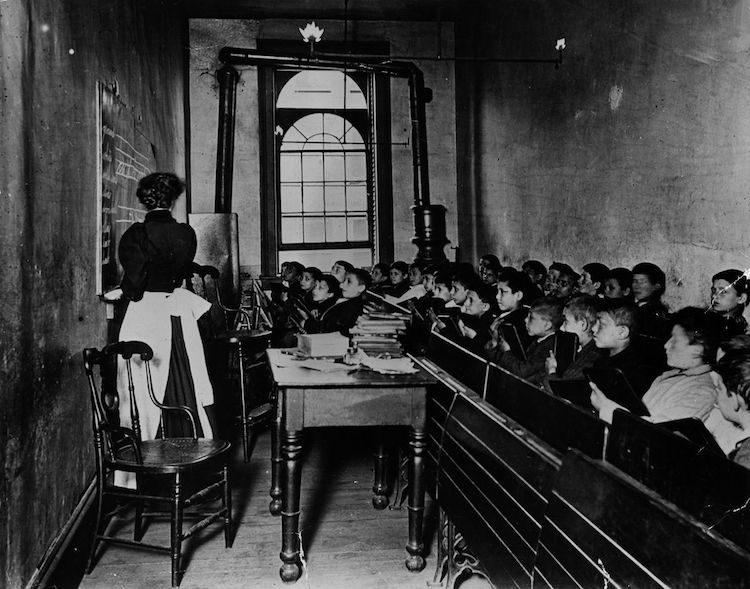

Riis published his photographs in a book, How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York.

Pupils in the Essex Market Schools in a Poor Quarter of New York

The Baby's Playground

This treatise brought attention to the issue and helped pioneer social reform in New York City.

Street Arabs in their Sleeping Quarters

Girl from the West 52 Street Industrial School

Boys from the Italian Quarter

Frequently Asked Questions

What was the purpose of How the Other Half Lives by Jacob Riis?

The purpose of How the Other Half Lives was to expose the plight, poverty, and hardships of immigrants in 19th-century New York City.

Who is Jacob Riis, and what did he do?

Jacob Riis was a writer and photojournalist who pioneered social reform through his photographs of everyday life in New York City's slums.

Who was the intended audience for How the Other Half Lives?

How the Other Half Lives was intended for people, particularly societal change-makers, to become aware of the unsafe living conditions that many people in New York City faced.

This article has been edited and updated.

Related Articles:

Vintage Photos Reveal the Gritty NYC Subway in the 70s and 80s

B&W Photos Give Firsthand Perspective of Daily Life in 1940s New York

50 Years of Meryl Meisler’s Iconic New York Nightlife Photography on Display

Leica Honors Legendary Photographer Elliott Erwitt With Its Hall of Fame Award